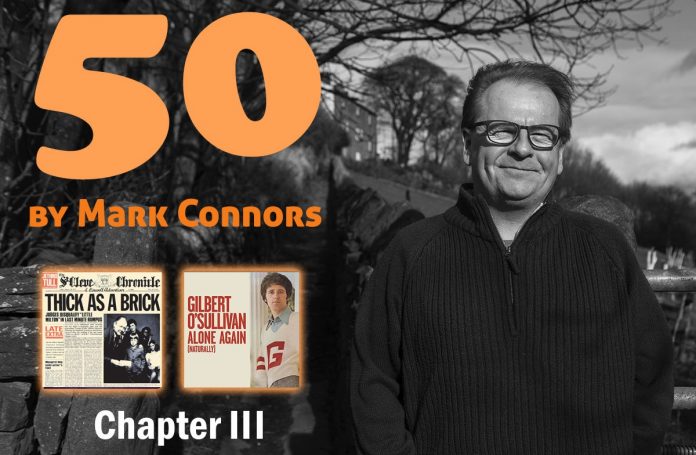

Chapter III of 50 by Mark Connors series. Mark talks about the Prog Rock album “Thick as a Brick” by Jethro Tull and “Alone Again and single Naturally” by Gilbert O’Sullivan

This is the third chapter of our 50 by Mark Connors series that takes us back to 1972 revisiting one of the most important albums of Jethro Tull and Gilbert O’Sullivan’s single “Alone Again (Naturally)”

1972 (Album) Thick as a Brick – Jethro Tull

If you tied a teenager to a chair and made them listen to Jethro Tull’s Thick as a Brick in its entirety, all two songs of it (but really one song in two parts for the practical reason of being cut on an album, back in the day) and then told the teenager that in 1972, this very album reached number one in the States and number five in the UK and that, after Led Zeppelin, they were pretty much the biggest band in the world at the time, that teenager would think you were either lying or you were utterly insane. But this was the early 70s, when people still had attention spans that lasted longer than four minutes. Or maybe it was because many of those who bought albums in the 70s couldn’t register how much time elapsed between the needle hitting the first groove and side one drawing to a close because most of them were off their tits on drugs. Either way, the early 70s was a golden era for Progressive rock.

And yet, Jethro Tull were not fans of the term and were irritated that their previous album, Aqualung had been labeled a concept album by the music press. After some early support from demigod DJ John Peel, who could help make or break a British band for three decades, the music press in general and Peel himself turned against Jethro Tull once they had started becoming a little too experimental. However, stateside their soaring popularity, sellout shows and record sales meant they could get away with pretty much anything. So, Ian Anderson, the genius behind Jethro Tull, decided to play a joke on both the music press and the concept album wielding Progressive rock bands they had been compartmentalised with. The resulting joke was Thick as a Brick, a parody if you will, a Monty Python-esque satire of a bloated musical from.

Ian Anderson, not a man to do things by halves, really went to town with his joke. The album cover comprised a fictional twelve page local newspaper telling the story of a young Gerald Bostock, complete with local news, obituaries, bizarre sport reports, even a review of the album itself. The album cover was even designed so you could unfold the original cover out into a mini newspaper. The contents of the album cover were pretty funny but the music on the disc inside was not. Unlike many prog albums, the lyrics were complex yet coherent, poetic even, with an engaging narrative and the music itself was mind blowing. If there was a joke at play here, it went over the heads of the Progressive rock fans who bought it in their millions. Ironically, the album became a defining moment for the very genre Jethro Tull were attempting to satirise.

The influences are there for all to hear: folk, jazz, blues, rock, classical, even metal; wonderful melodies, bewildering time signatures, and through it all a virtuoso flautist at the height of his considerable powers, who brought the whole thing together in often mesmerizing ways. If this was a joke, prog fans were too busy air-drumming, air-fluting, air-guitaring, singing along through one forty-five minute song of staggering originality to notice.

I didn’t come across Jethro Tull until 1988. I was a singer and lyricist in a band and I wanted to be influenced by more than the metal and rock I’d grown up with and was hungry for experimental music that would stretch and inform my own writing. I was already a fan of Rush, Yes and Marillion but Jethro Tull were a different proposition all together. Not better necessarily, but unlike anything I’d heard before. It was the flute what did it, Gov.

By this time, Jethro Tull had morphed into a Grammy-winning version of Dire Straits with flute (a no less engaging version of themselves I might add) and I remember being introduced to them by our guitarist, Graham. He played me MU The Best of Jethro Tull, a 70s retrospective of their work. I played the album to death. There was a three-minute excerpt of Thick as a Brick on side one and I was delighted to ascertain that there was another forty-three minutes extending the themes and motifs set out in this edited snippet to be found on an album of the same title. The first hearing of the album began a musical love affair with a band I still love to this day. Although 1971’s Aqualung is widely regarded as their finest recording, I for one, think their 1972 album just pips it. For nothing else, the cover of Thick as a Brick mentioned a certain pipe-smoking Derek Smalls, a name borrowed by Spinal Tap for their mustachioed band member. The delicious and complex irony of a band satirising a band who satirised other bands who they ended up out-progging is reason enough to crown Thick as a Brick as not only the best Jethro Tull album but the finest Progressive rock album too. That’s the thing most critics and haters don’t get about prog. It’s a musical genre comfortable with those who take the piss out of it and equally comfortable taking the piss out of itself. Unfortunately, the fans aren’t always in on the joke but continue to buy the albums anyway.

1972 (Single) Alone Again, Naturally – Gilbert O’Sullivan

If it’s not weird enough that Progressive rock albums sold in their millions in the early 70s, songs about suicide or contemplating suicide were pretty popular too. And these songs were really good, to boot. Along with Vincent by Don McLean discussed in my previous chapter, Gilbert O’Sullivan’s Alone Again (Naturally) was also a massive hit on both sides of the Atlantic. It went on to be covered by Neil Diamond and Shirley Bassey among others, to make O’Sullivan richer still. Not bad for a song with a fictional lyric about a man who gets jilted at the altar and promises to ‘treat’ himself by jumping to his death from a local landmark should his melancholy not dissipate. In the second verse, the narrator of the song questions the very existence of God before reflecting on the death of his parents in the third verse. If Gilbert had concluded his song with a chance meeting with the new love of his life, it might work as triumph over adversity type deal but the narrator just ends up alone and we don’t know whether he went on top himself or not.

I loved the song as a kid. Really loved it. So did my brothers and parents. It was regularly on the turntable in our living room on a Sunday, stacked up with other 45s that would drop in succession while Mum or Dad cooked the Sunday dinner. I bought his greatest hits album a few years ago and reacquainted myself with it and it flooded me with memories of growing up in the 70s. It didn’t feel particularly dated. It’s one of those timeless unusual songs which has inexplicably found its way onto the soundtrack of my life. The melody is beautiful. It’s got a great chorus and a soaring middle- eight and a pleasant and unexpected acoustic guitar solo.

I doubt such a song would reach the dizzy heights of the US charts today. Nor would a weird looking Irish geezer from Waterford with a set perm your granny would be proud of become a pop star. And why would changing your name from Ray to Gilbert possibly help you in your quest for domination in the pop charts, whether you were singing about topping yourself or not? Such are the mysteries of how to sell millions of records in the 70s. I blame it on the drugs.